1 Neillsville, Wisconsin

Rural America underwent its biggest changes in the first half of the twentieth century, long before I was born. From an economy that was 90% agriculture to our modern, urban one, what used to be considered the backbone of American culture has gradually faded into history.

Not for me.

Neillsville: A brief history

During the 1960s and 1970s, small farm-centered towns like Neillsville were already becoming marginalized in American culture, but the older residents – my teachers, civic leaders, and relatives – remained in a world that would have been recognizable a half-century before me.

By the time I was born in 1963, Neillsville’s main industry had long since switched to dairy farming, but that was a modern development. Settled originally in the 1840s, it was the plentiful forests and the promise of a lumber business that first brought James O’Neill here, building a sawmill on the creek that bears his name. By 1854 the community that had developed around it was important enough to be chosen as the county seat.

Lumber was an important business through the 1800s. The nearby Black River was in those days wide enough for commercial navigation, flowing through the heart of central Wisconsin all the way to the Mississippi River. As O’Neill’s Mill processed the plentiful oaks, chestnuts, elms, and birch of the forests into lumber, land was cleared for farming corn, oats, and soybeans, and hay for grazing animals, especially cows.

By the early twentieth century, much of Central Wisconsin was becoming a center for milk production, for cheese and butter-making, now exportable to the cities via the railways that crossed the state. Rolling hills and forests, punctuated by plentiful water from small streams and lakes made it ideal for dairy farming. The geography as well as the climate was familiar to north European immigrants from Germany and Scandinavia, who came in droves, attracted to the excellent farmland and not intimidated by the cold, long winters. These hearty settlers and their big families soon multiplied and integrated, so that by the time I arrived, the only memory of Europe was in the names: Shultz, Larsen, Elmhorst, Opelt, Makie, Mengle, Swensen, and dozens more names that were so common I assumed the whole United States was populated this way.

Most of these immigrants came originally by train, from the teeming drop-off places in Chicago. My grandparents spoke routinely of the importance of the trains in their childhoods, but the Neillsville train station had been long abandoned for passenger service by the time I was born. In decades past it was the only practical way out of town, for both people and freight. Central Wisconsin was littered with small towns that had once thrived but were now all-but-abandoned after the transition from rail to automobiles.

My seventh grade math teacher, Sam Ray, married to my first grade teacher, often told us stories about the Neillsville of his childhood in the 1920s and 30s, when having a car was a big deal, because it was possible to make the trek to a big city like Eau Claire in a half a day. But by now the roads were paved, cars were bigger and more reliable, and the same trip could be done in an hour.

Eau Claire was an important destination to us, and for most of my childhood it was the very definition of urban. My parents met there, at the Eau Claire State Teachers College, now the University of Wisconsin – Eau Claire Extension, so we had some familiarity with the place, but it was still considered a place to go on special occasions, no more than a few times a year. With a population of more than 60,000, it dwarfed any of the other places we could imagine visiting.

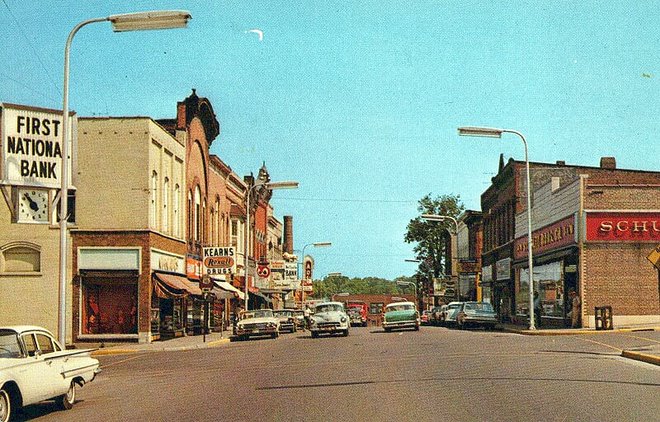

Neillsville, at 2,750 was itself the biggest city in Clark County (total population around 25,000), so we already thought of ourselves as a real city, unlike the smaller towns that dotted central Wisconsin: Greenwood, Granton, Hayward, Thorp, and many others. For shopping, you could buy most of what you needed in Neillsville. We had two grocery stores, a hardware store, car dealerships, furniture and department stores, a shoe store and more.

But still, for serious shopping, you would have to make the thirty-mile drive to Marshfield, which at 20,000 people made Neillsville seem small. Marshfield had traffic lights, fast food outlets (McDonalds! Kentucky Fried Chicken!) and even a tiny community college. Like Neillsville, Marshfield had a newspaper, but it published daily, not once per week.

Marshfield’s biggest employer, the Marshfield Clinic, was regarded as one of the better hospitals in the state, and possibly in the Midwest, attracting a small but important segment of well-educated doctors and medical practitioners, no doubt attracted by the small-town lifestyle in a natural setting.

That was our world: Neillsville, innumerable smaller nearby towns, the big city of Marshfield, and for very special occasions the huge metropolis of Eau Claire. The world beyond was, to us, mostly theoretical. There were the Really Big Cities, like Minneapolis and Chicago, and occasionally you would hear of somebody traveling there, perhaps to fly on an airplane (we didn’t know of any other way to travel by air). Our grandparents had met and married in Chicago, but left soon after that, and had nothing good to say about the place. Our uncle insisted that, if you ever find yourself needing to drive a route that takes you past Chicago, whatever you do, don’t go through the city.

That was fine advice, as far as I was concerned, though frankly a bit irrelevant. Why on earth would anyone need to visit a big city like Chicago when we had everything we needed right here?

1.1 Farmers

Neillsville since the 1960s and 70s has seen less change than many American places, if only because its rural location makes it too easy for the rest of the world to pass it by. The population when I was there, two thousand seven hundred and fifty, is about what it is today.

The 1980s were tough on rural agricultural towns like Neillsville, and many of the ways that Neillsville could be proud of itself went away. I’ve been back a few times since, but not enough to understand the subtler changes so it’s just my speculation that the general quality of the people has changed.

Dairy farming, and the agricultural life in general, was the defining pillar of the community. By the time I grew up, America had already shifted from an economy based on farmers, but that was all theoretical to us then. Today it’s hard to imagine, but my brother and I were considered “city boys” by the local standards. But even us city boys were very familiar with the smells and activity of a farm: the moist pungency of cows in a barn, the thick overhang of pollen in the hay fields, the long, hilly dirt roads out of town with red barns sprinkled lightly through forests and never-ending corn fields.

In middle school, out of emerging teenage spite, I chided one of my friends, a farmer’s son, that the world doesn’t really need farmers. “We’d find some other way to get food,” I insisted. I was imagining robotic planting and harvesting machines, maybe, or a world of genetic modifications and food grown in factory vats. Science, I thought would eventually make obsolete the old-fashioned, primitive ways of growing food. At the time, I meant this in a provocative, maybe mean-spirited and certainly immature way, but in the larger sense now I guess I was on to something.

Farmers today, even in Neillsville, are endangered. Yes, there are people who make a living from tilling the soil and raising cows, but more likely than not, they are employees of corporations, the big and efficient companies that now run agriculture like factories. Neillsville now boasts several of these multi-thousand acre enterprises, with a staff of specialists: a full-time expert for example whose only job is to determine which crops to plant in which field; a team of veterinarians to look after the herds; a foreman – maybe a group of them – looking after the dozens or hundreds of unskilled hands hired to do the menial and still labor-intensive jobs of putting up and repairing fences, driving tractors up and down fields, attaching and releasing milking equipment twice each day from row after row of cows. Those are not the farmers I remember.

My farmer friends were all families. You could say they were “family businesses” but the word “business” seems awkward somehow and not really applicable to people to whom this was a way of life. Our friends weren’t milking the cows in order to earn a living – though of course that was the net result. They were farmers because their parents were, and because that was what you had to do in order to eat. You can’t be a farmer if, to you, it’s a “job”; it’s a lifestyle. The farmers I remember got up in the morning to milk the cows, not out of any consciously expressed purpose (“it’s my job”) but because that’s just the way it is. Why do city-dwellers clean up their dishes after dinner? Why does a man in the suburbs mow his lawn? They do it because it’s something that has to be done. It would never occur to a farmer to think of his occupation as a “career”, in the sense that, oh I’ll just do this for a few years and then submit my resume to some company and switch to a different job. Farming, to a real farmer, is life itself.

On my, sadly, infrequent visits back to Neillsville since that time I find that few of my friends remained in farming. Farmers children nearly all went to college, it seems, and even those who majored in “agricultural studies”, ended up mostly in the cities, in other occupations. The few who remained behind, keeping up the family farms have migrated to organic farming, where the profit margins are higher, and where the benefits of direct attention to the farm is greater.

1.2 Tourism

Despite its central location geographically, Neillsville is about 30 miles from the nearest interstate highway, putting it almost three hours drive from the nearest big urban area of Minneapolis-St. Paul, and almost six hours from Chicago. That’s an impractical distance for day trips, so to attract visitors and their tourist money Neillsville has had to invest in various attractions, with varying levels of success.

There’s the natural beauty of course: rolling green hills in the summer, colorful leaves in the fall, white powder trails perfect for snow sports in the winter. When the Ice Age receded, it left a large moraine just outside of town, the top of which presented a beautiful view of the Wisconsin countryside. Sometime after I left in the 1980s, it was turned into a Vietnam Veterans memorial and today draws thousands of visitors a month.

On some measures, Neillsville could even beat our nearest big city of Marshfield: we had a radio station, WCCN (the call letters stand for “Clark County Neillsville”). The Clark County Jailhouse, now a museum, is listed in the US Register of Historical places.

But no other town has anything to compare to our biggest tourist attraction: the “world’s largest cheese”, housed in a special exhibit at the edge of town, a monument built for the 1964 New York World’s Fair. As if that weren’t enough to attract tourists, the occasion was further memorialized with a large outdoor statue of a cow in its honor. “Chatty Belle”, complete with a speaker and audio player will, upon deposit of a quarter, regale any visitor with a short missive about the wonders of our town.

Such was the tourism industry in Neillsville, and I guess it was reasonably successful since the “talking cow” and nearby Worlds Fair Pavilion are still there.

1.3 Daily life in the 1970s

It’s hard for my kids to understand some of the basic ways that life has changed since I was their age.

1.3.1 Telephones

My parents and grandparents could remember when their homes got their first telephones. Very few families had more than one, usually a standard black rotary dial, often in the kitchen, shared among all the family members. When that phone was in use, an outside caller trying to reach the home would get a busy signal; no calls could be received until current call ended. We had no voicemail or answering machines either; if you called somebody and there was no answer, you’d have to call again and hope they were home the next time. Worse, there was no way to tell that a call had been made, or who it was from. If you heard the phone ring but didn’t answer it in time, you’d never learn the caller’s identity unless they dialed again.

Local phone calls were free. Since this included most locations in Clark County, my mother could call my grandmother regularly without worrying about the cost, but anything more distant required a per-minute charge. The fees to places in the Midwest were fairly reasonable – maybe a few cents every ten minutes? – but more distant locations and the charges could really add up. A call to friends or relatives out of state might cost a dollar or something per hour – the equivalent of, say, $5 or $10 today. This was something you might do on a special occasion – a birthday, Christmas, or perhaps after a funeral or birth – but generally we didn’t call unless it was very important.

Fortunately – or perhaps, as a result of this – we didn’t have many friends or family that were distant enough that this would matter.

Instead we relied on the mail. Much, perhaps most, communication with people outside of Neillsville occurred through the post. I wrote many letters, and postcards, and received many more. The mailbox was my lifeline to the world.

1.3.2 Information

Our news about the world came from radio, TV, newspapers, and magazines.

Popular or common titles were available at some of the stores in Neillsville, but for more specific books you’d have to go elsewhere. There was a bookstore in the Marshfield Mall that stocked a full variety of books.

It’s hard to overstate the importance of libraries. Our public library was small and underfunded, but it was accessible to everyone. The high school library was much better, and it was a delight when I was finally old enough to be allowed admission. Later I was also able to peek at even bigger libraries, in Marshfield and then Eau Claire. The amount of information was staggering!

Even basic facts – the kind that anyone gets today from the internet – required serious research. What’s the population of Wisconsin? What year was the Civil War? How do you best treat a cold? Answers required finding and looking it up in the appropriate book.

One treasure trove of knowledge was the Encyclopedia Britannica, which my family was fortunate to have at our house. Sprawling along our bookshelves in ten or fifteen volumes, you could get a short summary of all the world’s knowledge. Of course, it was nothing like the depth of today’s Wikipedia, but it was well-written and approachable. I remember spending hours sprawled out on the floor digesting articles about everything.

For shorter, factual answers we had almanacs and other specialized reference books like dictionaries or The Guinness Book of Records. If, in the course of a discussion or homework assignment you needed to know a fact, you had to crawl across the room and open the book. If it wasn’t in the book, you had to visit the library. And if it wasn’t at the library, then your only choices were to give up the search or – and I did this occasionally – write a letter to some expert and hope for a reply weeks later.

We also had maps, bound as an atlas for a broad survey, or roadmaps that were useful for traveling. Paper maps, road signs, and spoken directions were the only way to know how to get to your destination.

Finally, there was the phone book, which was useful for more than simply finding a phone number. These books – distributed annually for free to all households – contained lists of businesses printed on yellow paper. These “yellow pages” were organized by subject and included paid advertisements for businesses. If you needed a plumber or electrician, or you wanted to know which churches are in town, your first stop was the yellow pages.

1.3.3 Photography

Cameras were widely available at prices that anyone could afford, and we took plenty of photos. But to today’s generation, raised on high-quality images and video from mobile smartphones, our photography was incredibly primitive.

The camera itself was cheap and if you couldn’t afford a commercial model it was easy to make your own. Once summer we made a “pinhole” camera out of cardboard and successfully took photos that I have to this day.

No matter what camera you had, the photos themselves required a separate purchase of photographic film. You could buy film canisters, usually in rolls of 24 or 36 images for reasonable prices – a few dollars. But, importantly, you couldn’t view the images until after they were processed – a separate step that required weeks of waiting and additional money. All told, a single photo might cost between $0.25 and $0.50 – not a trivial amount of money in a world with a $3-$5 hourly wage. Because you had to take photos in increments of 24 or more, this often meant that some events didn’t get viewed until months later.

Although it wasn’t unheard of for people to process their own photos in a home “dark room”, mostly we dropped our film at the pharmacy, or mailed it to a mail-order lab that would send the developed prints back to us within a week or two.

The significant, weeks-long lag between taking the photo and seeing the results made for special moments when at last we received the final images.

Sometime in the 1970s, Polaroid’s instant photo cameras became widely available. To us, these were revolutionary because they let everyone enjoy the images within minutes. The downside: each photo was more expensive, on the order of $1. In today’s money and relative purchasing power, that would feel like closer to $5 for a single image.

As you can imagine, at those prices each photo was precious and we tended to take them only on special occasions.

1.3.4 Food

An agricultural community contains abundant reminders of food everywhere: the big farms with their cornfields and pastureland, of course, but also in our day-to-day lives. Everyone we knew had a vegetable garden. Fishing and hunting were popular activities, and not just for sport: many families proudly supplemented their pantries with food they had caught themselves.

By today’s standards we would have been considered locavores or even organic, because most of what we ate was grown nearby. This wasn’t necessarily by choice: I don’t remember caring where the food came from. That just wasn’t important to us.

We ate plenty of non-local food: packaged goods like breakfast cereals, canned goods shipped from elsewhere, or orange juice from concentrate. During the winters we had no choice, but by mid- and late-summer, we were eating fresh local produce like lettuce and green beans.

As you’d expect from a dairy-dominated location, we drank a lot of milk. We ate cheese too, of course, but nothing like the variety you see today in an upscale supermarket. For us, cheese was always yellow-orange and came in exactly two varieties: cheddar and Colby. It was a source of some pride that Colby had been invented in the nearby town of Colby Wisconsin.

Like most adults, my parents drank coffee, usually purchased in large tin cans of ground beans from national brands like Folgers or Maxwell House. In those days, long before the founding of Starbucks and its minions of boutique imitators, coffee was coffee. Terms like “latte” and “espresso” were literally foreign to us.

For some reason, despite being surrounded by coffee drinkers, my siblings and I never picked up the habit. I assume my parents offered it to us as we got older, but it never occurred to me to try it.

Typical meals

Breakfast was some type of cereal with milk. Corn flakes and Cheerios were probably the most common and popular. My family always had those boxes on hand, served poured into a bowl with fresh full-fat milk. My mother taught us to sprinkle a bit of sugar on top as a special treat.

In our house we often ate hot cereals, usually oatmeal served with milk and perhaps brown sugar. My mother sometimes made other hot cereals, like Ralston or Cream of Wheat.

Bacon and eggs were another standard, especially when visiting grandparents. On Saturdays we often had pancakes as well, usually served with a corn syrup sweetener like Aunt Jemima or another “maple-flavored” topping. Although we had access to fresh, local maple syrup, for some reason my siblings and I thought it tasted like medicine and we refused to eat it.

We referred to our mid-day meal as “dinner” and this was often a sandwich of some kind. Cheese was common, perhaps served with sliced meats like turkey or ham or roast beef. My mother taught us to spread a leaf or two of iceberg lettuce on top, though I generally refused the mayonnaise or mustard that she suggested.

The final meal of the day we called “supper”, and in my family it was typically some type of meat – often beef, pork, or chicken – with reheated canned vegetables like peas or green beans. We ate this with store-bought sliced bread, preferably as bleached white as possible.

My mother often cooked potatoes, usually mashed and topped with generous amounts of butter. Beef roast was a common meal, cooked to perfection in her electric oven.

At my grandmother Pulokas’ house, the bread was always homemade, usually a dark rye or whole wheat bread. My grandfather preferred thick crusts, served with copious amounts of freshly churned butter.

For fruit, either as a snack or served with a meal, we ate apples (usually red delicious, but often a variety from a local tree), pears, and perhaps other fruits gathered locally, like raspberries, blueberries, or strawberries in season. The grocery stores stocked plenty of imported, cheap bananas year round. In season we could also get fresh peaches, cherries, oranges and grapefruit. Some of those fruits might be available at other times of the year, but always at exorbitant prices.

Snacks were simpler than today. My mother would regularly bake cookies, brownies, or pies, and leftovers were always available. To top off the calories required by the teenage boys of the household, we also ate boxes of packaged snacks, like Oreo Cookies, Fritos Corn Chips, and Twinkies. I don’t think the idea of “healthy snacks” would have occurred to us. Like dessert, the whole point was to have something that tasted good.

I remember the day our family bought a dishwasher. Before that, everything was washed by hand, and usually hand-dried too with a towel. Visiting Grandma Pulokas it was a treat to be assigned the drying duties, but I don’t remember doing this at home. Maybe it was a duty related to my sister and mother.

Microwave ovens were exotic and expensive, so we didn’t have one but the Gungors did. It was a treat to try putting different foods in the microwave to see what would happen.

Restaurants were not nearly as common as they are today. Although Neillsville had exactly two competing fast food places – the A&W and another ice cream shop called The Penguin – and one or two cafes that served lunches, I don’t remember anything that today would be considered a fancy “sit-down” or white tablecloth restaurant.

Central and Northern Wisconsin were known for their “supper clubs”, a sort of combination restaurant - tavern - gathering hall, often used for weddings or other receptions. These places served food similar to what most people enjoyed at home: meat roasts, fried chicken or fish, potatoes, canned vegetables. Our family strictly forbade alcohol, so we wouldn’t have visited places that served it, but I imagine it was common for supper clubs to offer local Wisconsin beer in cans or bottles.

1.4 Small town neighborhood

We lived in an old, two-story house on Oak Street, surrounded by a diverse mix of neighbors, many of them families with children my age. Our next door neighbor was a postman with two children a bit older than us, including a teenage daughter who occasionally babysat. We had a few elderly widows, including Mrs. Demert, who wrapped her tiny Chihuahua puppy into a snug hand-knit body suit before his daily walks in the cold Wisconsin winters. There was Mrs. Fry, who lived alone except during the summer months when I saw my first taste of California, a license plate on a car parked in front of her house that carried a load of grandchildren. We had the Carters, a family of Sixties-era hippies, who apparently used drugs enough that my mother used their name as a superlative: “…more X than Carters have pills.”

We knew everyone: lawyers, doctors, schoolteachers, the town barber and his kids, a fireman and his family, small business owners including the grocery store, hardware store, a furniture store, and much more. And while of course there were differences in wealth among all of us, we all lived in similar-sized houses and the children attended the same schools.

Well, most of us did. Even a small town like Neillsville had private parochial elementary schools: St. Mary’s Catholic, and St. John’s Lutheran, Bible Baptist. But any educational differences had to do only with religion, which to outsiders would have seemed tediously arcane among Christian people who agree on far more than they disagree. We didn’t know there could be secular private schools for wealthy kids, or even specialized schools for people whose parents had enough money to pay to have kids focus on, say, the arts, or to get an education surrounded by other rich kids. We just didn’t know that world existed.

Politically, as can be expected from a small Midwestern town, most people seemed sympathetic to the Republican Party, but it was by no means a shut-out, in the way that Democrats exclusively dominate urban areas or university campuses in the rest of America. You would not draw attention to yourself by having it be known publicly that were a Republican in my small town – any more than anyone would think you were extreme for being a Democrat – but you would be better off keeping your views mostly to yourself, because you couldn’t assume that the others around you would agree with you.

The US Supreme Court ruling that prohibited prayer in classrooms was only a decade or so old by the time I was in school, so although we didn’t overtly pray (I’m not sure in Neillsville the schools ever did) it certainly wouldn’t have been the kind of thing parents would have complained about. My kindergarten teacher led us to say grace before our snack time, though it’s likely that she did this because most of the kids said grace at home, and it would have been completely natural to pray at school too.

My friends included people like Roberta, the girl who seemed perpetually happy. Or Roger, the big-boned farm boy who, like many others in our class, always smelled of freshly-milked cows.

I knew that my family was poorer than some families – and better-off than others – but at the time it seemed less about money than about priorities. Some of the houses boasted prettier, well-manicured lawns, but we had a bigger backyard garden. Some people had nicer furniture and carpeting, bigger TV sets or newer cars. But nothing about any of their lifestyles seemed beyond the reach of my own family. Occasionally we’d hear about somebody going on a big vacation, maybe by airplane to a faraway tropical island, and that seemed like the peak of luxury, but my family went on vacations too. Maybe we didn’t travel by airplane or stay in fancy or expensive hotels, but we could go where we wanted. Who needs money when you can stay with relatives or camped in a tent along the way, eating sandwiches and canned food.

At school, the differences in wealth or prestige didn’t matter a bit. The “rich kids”, children of lawyers and doctors, ate the same school lunch that we did. If they brought their own, it might have come in a fancier cartoon-labeled lunchbox while mine was a paper sack, but the contents were the same. A tiny handful of kids were rumored to have subsidized or free lunch. These were invariably victims of tragedy: the family whose home had been destroyed by fire, the kids whose father died in a boat accident, or the big family outside town who parents didn’t seem to be normal (maybe they were mentally handicapped?). Even then, to be on some type of public assistance was something everyone –including the recipients – viewed as disastrous, a shameful hardship for all involved and definitely just a temporary stepping stone on the way to self-sufficiency.

If there was a correlation between family status and school performance, it wasn’t a strong one. With few exceptions, everyone came from intact families – a father and mother – and the family attitude toward education probably affected school results as much as anything. When I discovered early in first grade that I tended to do well in school compared to the rest of the class, I found that my chief competitors were the children of schoolteachers or those whose parents had been to college. Even then, any link to the parents seemed tenuous, because I could always find exceptions, and of course academic performance was only one of many ways to measure the students. Some were better athletes or artists, some were more social. But we all attended the same school, and learned the same things.

The Neillsville Public Schools were located on a single tract of land on the east side of town, eventually consolidated into a single building. You entered the east doors for Kindergarten and graduated out of the west doors for high school. We had roughly 100 kids in each grade, split among four or five teachers. A small administrative staff rounded out the school with dedicated art and music teachers in elementary school, and more specialized teachers in high school. Although the place seemed huge to me at the time, the faculty – especially the longer-served ones – knew pretty much every student, if not directly then from teaching siblings.

Our religion dominated our lives so much that I don’t remember many friends from elementary school who didn’t have a connection to church, but we had neighbors, and like all kids I suppose it was only natural to find ways to play with them.

Although technically we lived in a city (the largest, the capitol city, of Clark County!), our neighborhood (like every neighborhood, come to think of it) was on the outskirts of town. An elderly philanthropist, Kurt Listeman, had donated some land to the city long ago as an arboretum, a large undeveloped forest with some trails carved into it, running along a scenic path to the nearby Black River. It wasn’t the kind of place that today I’d call a “hiking trail”, but to our pre-teen minds, it was the ideal place for play, especially on endless summer days in a world before parents thought to overschedule their children in “day camps”. Everything we did, we had to invent for ourselves.

In the large, overgrown field that separated our backyard from the arboretum, we found plenty of other neighborhood children who had come to play, and in time we invented a game we called “all day game”. If you showed up sometime in the morning, you’d find children from throughout the neighborhood, usually divided into teams of some sort, all playing an elaborate version of hide-and-seek. We imagined that the other neighbors were from a hostile foreign country, or that we were spies sent to penetrate the defenses of the enemy, or that they were invaders intent on destroying us. We rarely came face-to-face with the enemy; we usually only saw them from a distance.

Occasionally one side would spot the other at a sufficient distance to plan a surprise “attack”, creeping slowly through the underbrush just to the point of the other camp, sticks and stones in hand, ready to deliver a beating. Inevitably, the opposing side would discover the attack just in time either to flee or to counter-attack, depending on the whim of the players. The counter-attack, of course, would result in reverse behavior: once a side discovered it was about to be raided, they would themselves need to flee or counter-counter the attack, depending on the circumstances, precipitating even more fun of the chase.

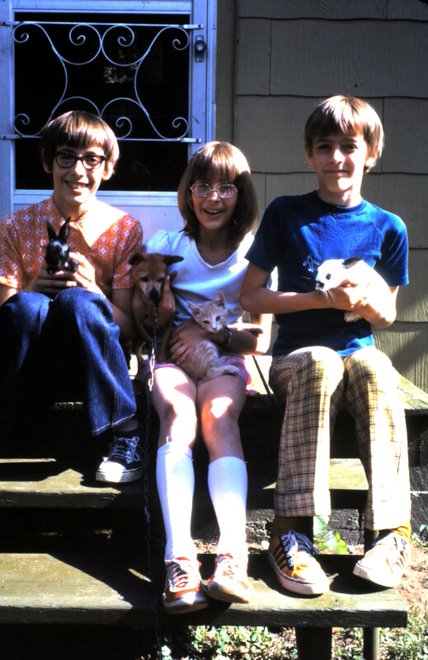

These games really did last all day, and everyone in the neighborhood seemed to join. Usually it was my family—both brother and sister – plus the Gungors, the Shorts, the Frys, and many others. The kids who we didn’t know from church, we knew from school – or if they were in different classes, we at least knew of them – so it was easy to identify our “enemies” by name.

Part of being away from home, running through the woods, all day was that obviously our parents (i.e. mothers – the mothers were all stay-at-home) wouldn’t be watching us. Nowadays such inattention would be unthinkable: what responsible parent wouldn’t know exactly where a pre-teen child is? But our mothers interpreted our absence as a sign we were happy and self-sufficient. They knew we’d be home eventually, if not for treatment of the occasional scrape or bruise, then certainly in time for dinner. My mother’s only rule, at least until we were older, was that we were not to go near the river itself. She knew too many personal examples of children who had drowned. In fact, one boy in our neighborhood did drown, and we knew of at least one other kid at school who unsuccessfully tried to rescue his younger brother who had fallen in during the springtime. So we stayed away from the river. But the rest of the woods was fair game and we took full advantage of it.

On one particular day, during an especially long forage into the woods, I remember we stumbled upon a group of much older teenagers hiding an illicit stash of beer, cigarettes, and who knows what else. At first were afraid they might try to hurt us for having discovered their evil den of sin, but the beer had apparently put them in a happy mood, so instead they just laughed at us.

Otherwise mostly what we found in the woods were trees (good for building forts and hideouts), sticks (good for make-shift weapons), and the occasional baby bird or animal (good for bringing home as an adopted pet). It was endless, nonstop adventure.

1.5 Neillsville People

If you’ve only lived in big cities, you might think that everyone knows each other in such a small town. That’s not quite true – even with fewer than three thousand people, nobody knows everyone. But much of the population has been there for generations, and long-time residents can find a connection with just about anyone. With fewer than 100 kids in each grade, anyone associated with the school system will know somebody with common family names. You could also identify people by their occupation (farmer, hospital worker, teacher) or by their church.

1.5.1 Our Friends

I no longer remember precisely when the Miller family arrived in Neillsville. The father, Dan Miller, was a woodcutter who raised his family in Athelstane, a small rural town on the way to Upper Michigan. The oldest was a boy, David, who towered over his four younger sisters. The parents were serious Christians who attended our church regularly, and the older kids matched ages with ours, so we naturally came to know them well.

Dave Miller and my brother loved many of the same things: cars, motorbikes, fixing things – all guy stuff. I think there was much friendly competition between them over who could their various guy hobbies, so they leapfrogged each other through high school buying and then fixing up old cars. Though Dave was deep down a serious, well-meaning boy, he had more tolerance for risk-taking than either my brother or me, and we looked at him as living right at the edge of lawlessness.

It’s funny to reflect on this now, because by any of today’s standards, Dave would be squeaky clean, but we saw him as a bold and daring ne’er-do-well. My brother enjoyed dirt-biking as much as any boy, but Dave’s ability to tolerate high speeds and dangerous situations topped anything we would have attempted. Where the rest of us (especially me) were barely willing to go up and down hills, Dave thought nothing of flying his bike right over a cliff. We joked about how crazy he could be.

His father, a straight-and-narrow pillar of the church, gave Dave little room to get into trouble at home, but school was another matter. Events reached a head one day when Dave did something so egregious (I don’t remember precisely) that, as punishment, Dave’s father decided to join Dave at school for the day. Obviously nothing could possibly be as mortifying to a young teenager, and he complained about it for years, but that I suppose was the father’s intention.

It may have been his status as an only boy in a family of sisters, but he seemed more comfortable – eager – to be around girls than we were. He was not afraid, like we were, to ask a girl out, or to take her for a long ride in his car, and later he would brag – just us guys – about what he had been able to get the girl to do.

Like most teenage stories, I doubt the reality was anywhere close to the imagined bravado when they were told, but Dave was a risk-taker in other areas so who knows.

He fell head over heels in love with a girl from another town, and he talked constantly about wanting to see her. He even changed his car license plates to “NADEEN”, which of course we thought was ridiculously short-sighted.

But then I remember one day, a Wednesday evening after church, when we normally had time to go over his most recent exploits, Dave confessed to us that he was no longer interested in misbehaving. “I don’t want to go to Hell,” he said, a point that we took more seriously coming from a boy who till then didn’t seem to consider the consequences of his risk-taking.

Dave married Nadeen a few years later and literally lived happily ever after – last I checked they’ve been together for more than 30 years.

1.5.2 Neillsville Friends

Maria Marks was one of half a dozen, maybe more, children in a family that attended our church. She had an older sister who I know worked far away at our Christian summer camp, and a younger brother who was a year older than me. The mom was an elderly woman who, I’m sorry to recall, sticks in my memory because her body odor was so overpowering that eventually somebody had to intervene and ask her to bathe before coming to church.

Maria was a nurse, probably in her late 20s, maybe 30s by the time I knew her, and very single. She wanted badly to be married, and I don’t blame her: she would have made a wonderful mother and I’m sure she wanted a family more than anything. She was also a very devout Christian, pure and sweet and loving.

After living in Neillsville for so long, she apparently decided that she was unlikely to meet a suitable husband there and so she took a chance and moved to Alaska on a one (or two?) year missionary program that involved some church-related initiative. I didn’t hear much about how it went, but i’m sure it was quite the adventure. Nevertheless when the assignment finished, she returned to Neillsville, unmarried and a bit older.

Sometime after this, a man named Joseph began to regularly attend our church. I’m not sure how he happened to come here — maybe he was related to somebody? — but he was very taken with Maria and began to pursue her. It was clear to us outsiders that the two were not a particularly good match, notably due to his rather large girth. He was very obese, not especially attractive. I don’t know that he had any other qualities that would make him ordinarily somebody she would seek, but apparently none of this mattered relative to his charm. He did everything to make her feel like he would be a good husband. One night at church, after I guess they were a thing, he testified how much weight he had lost since meeting her — proof, he believed that God wanted them together.

Long story short, they married and last I heard are still together, though childless. A real shame, because Maria would have made such a good mother.

Mark was a boy my age, who lived about a block beyond Jimbo’s house. Mark was well-liked and intelligent, and although our paths crossed regularly, I don’t remember any particular incidents that would have made us close friends. Everyone knew everyone, so my memories of him don’t stand out for anything in particular.

He was a budding filmmaker, in the same way that I was obsessed with computers, but like me, he had to live within the constraints of the technologies of the times. Still, using what today would be unthinkably primitive techniques, he was able to make some interesting home movies, often about his favorite theme: space travel. We were all heavily influenced by Star Trek and later, Star Wars, but Mark brought his interest to the rest of us, writing short movie scripts, and then directing them using the consumer film movie cameras of the day. (Later posted to YouTube)

I don’t remember how he met Julie, his high school sweetheart, but whatever it was, the two of them are inseparable now in my memory. I think they attended the same college (Eau Claire) and then married within a few years of high school and they were still together 40 years later.

Right out of college, Mark and Julie started “Ag News Network”, a radio program with daily updates relevant to farmers. I lost track after leaving Neillsville, but it apparently didn’t last very long because the next time I heard about them, they were living in Minneapolis. I think he worked at a bank for a long time, until he took advantage of a layoff package to start his own marketing business.

Along the way, I remember that he won some kind of screenplay contest that let him pitch in front of the makers of Star Trek. I read the script at the time and thought it was very original, very well-done, although it apparently never made it to a contract. He self-published a book too.

1.5.3 Small Town Low Life

The knowledge that our parents loved us was a deeply-ingrained fact, like air, and like wind sometimes something to resist. Of course, parents should love and care for their children – no exceptions – but we also knew that not all families could take that for granted.

Neillsville was a small town, and it was possible – just – to know something about everyone. Even among those we didn’t know directly, there was a connection not far removed, and gossip was plentiful. As kids, we were well-protected from the worst of humanity, but that didn’t mean we were wholly unaware. Years later, when I could understand the bigger truths, I could see that sometimes when things aren’t quite right, there was a deeper problem.

One of the girls in eighth grade left school because she was pregnant. She had always been quiet, not a particularly good student, with few friends, so we didn’t notice too much. I remembered how, years earlier in fourth or fifth grade, while playing some kind of game of tag at school, she and another girl had tackled me. It was all just fun, so at the time I just thought it was rather odd, not malicious, that she grabbed my groin and squeezed me. This hadn’t happened to me before – touching that way was considered more gross than inappropriate – and the game was too fast to dwell on such oddities, so I attributed it to normal roughhousing. It wasn’t until years later that I learned that her pregnancy was a result of incest, an apparent rape by her father.

Then there was a boy who seemed to prefer to play with girls. Again, we didn’t see this as particularly shameful or undesirable. In kindergarten I preferred the quieter games of the girls too sometimes, and this boy didn’t exclude boys – we played with him too. He just seemed like he felt more comfortable around the girls, and he was otherwise fairly friendly and interesting so we didn’t think anything of it.

Years later, the town optometrist – an otherwise well-respected neighbor who we all knew as “normal” – committed suicide. He shot himself in his basement, having left a thoughtful note to his wife warning her not to come downstairs. It turned out that this man had regularly invited that boy alone to his house, showing him pornographic movies in his downstairs theatre.

We all know what we mean when we say “small town values”: nuclear families with a working father and stay-at-home mom, active in the community including regular church attendance, hard working, clean living, even short haircuts for men and boys and always long hair and dresses for the girls. Popular movies and sitcoms often hold these stereotypes up for ridicule as a repressive society drenched with hypocrisy: the church-going father who beats his wife and children, the gay-bashing minister with the secret homosexual affair, the abstinence club run by the school slut.

Nobody uses the word “big city values”, because the only difference, it seems between the secret alleged sins of the small town is that the city people are open about it, unashamed, even proud of their immoral ways. “At least we’re not hypocrites,” they say in smug judgment of the small-towners.

But I think the difference is not one of hypocrisy but aspiration. Nobody in a small town believes that people are always righteous and good or that sin is limited to big cities. Maybe it’s the direct experience with sin and its personal, individual affect on people that makes a small town more averse to such habits. Of course we sin, but we really wish we didn’t. If the city people want to claim that their bad behaviors are actually good, then that’s the part we don’t understand because we know from first-hand experience the wages of sin.

I learned about infidelity long after I left, because as a teenager I guess it never occurred to me that people could run into trouble later in life. We knew that husbands could cheat on their wives, of course, but it seemed like something that only happened to those who weren’t active in the church.

Our high school guidance counselor, for example, was always friendly, active in the community, a great resource for kids who didn’t know what they wanted to do after high school. His wife was the most popular teacher in fourth grade; Gary had her, and their policy of spreading siblings out among different teachers was the reason I was passed over for selection into her class, which seemed so much more full of interesting projects and great teaching than the comparatively dull class I was assigned.

A few years after I had left, we learned that this same guidance counselor and his wife had abruptly quit town, moving far away after it was discovered that he had been having an affair with one of the high school girls. Everyone knew the girl well, of course; she was popular and outgoing. If he had been a high school student himself, we would have thought the two made a great, natural couple. But clearly, something had not been right all along.

Many other examples: our high school history teacher, who abandoned his wife and teenage daughter for an affair with another teacher. The math teacher who, besides algebra and geometry, taught me by example the harsh and lonely world of an alcoholic, and that unforgettable, medicinal smell of alcohol on his breath. The town banker, pillar of the community, who after forty years of marriage ran off and then remarried a younger woman. But at his funeral, it was his original wife and their many children who mourned him most.

George Williams lived around the corner from us with his postcard family. His wife was the always-prim daughter of one of the founding families of Marshfield, and they had two children, a boy and girl who attended our church and we knew well. George was by all accounts a successful businessman, owner of the local appliance store, and lead accordionist in a popular polka band. Though he himself wasn’t an enthusiastic Christian, his wife attended our church regularly and the kids were raised just like me. Sometime after I left, his business failed and he was forced to move to Marshfield. Who knows if that was the cause or the consequence, but sometime after that we learned about an ugly affair, and his tragic divorce. Although nothing about the situation would have made sense to me at the time, I could somewhat explain it by the fact that he wasn’t, perhaps, as enthusiastic a Christian as others.

Bill Smith, on the other hand, had no such excuse. An active outdoorsman and leader in our scouting group, he was by all accounts a loving husband, father of three boys, and deeply-believing Christian. A few years after I left Neillsville, we learned that he had been involved with a woman who had been renting a trailer home from him. His wife discovered it by accident when, upon opening a Christmas card addressed to him, saw that it was signed by “your other wife”. Turns out this renter was herself an enthusiastic Christian, and the affair started over various theological conversations they’d had when he visited her to check on the property.

Then there was Steve, one of my favorite Sunday school teacher friends, a simple electrician who inspired me with his eager interest in all things intellectual, far beyond what you’d expect from a small town laborer who’d never been to college. To this day, he is proof to me that the world is full of people, in places you’d least expect, who are meant for bigger and better things but whose circumstances somehow never arrived.

His wife, Jill, is best described with the word “loud”. She seemed his opposite: the type of person who prefers to think while talking, and although she talks much, the signal to noise ratio is, well, low. But she was a kind, cheerful person and a good mother to their son.

When I last saw them in person, they were fretting over their (now adult) son’s involvement in a relationship with a much older woman. Steve, I remember, was not fooled when the son insisted that he had to stay overnight on her couch because he couldn’t get the car to start. “I wouldn’t have stayed on the couch if I had been you,” he said. But with the son out of the house and on his own, there wasn’t much else they could do, and Jill had other things on her mind anyway: she wanted to leave town and move to Mexico for a while to live with some missionaries. She wanted Steve to join her, but he was reluctant.

I learned later that in fact, Steve did ultimately come along with her, but that somehow in Mexico he became involved with a woman. Jill didn’t find out until much later, at which point they of course divorced, as things go in a small town. By then he was apparently fed up with her completely because he soon found another girlfriend, online, a mail order Asian bride back to America. Now Steve is settled with the new woman, a few houses down from Jill, crossing paths regularly with townspeople who knew him from his youth, but apparently he simply doesn’t care. The last I talked with him, he had completely renounced his faith and was reading and studying progressive politics and ideas – a complete change from when I knew him and a bit sad.

All of these episodes taught me more about human nature and about how the world really works. There was great good in Neillsville and great evil, with the good always slightly ahead of the evil.

Our community didn’t have much illegal drug use, at least as far as I knew. Sure, there were the “bad kids” who went behind the bleachers to smoke cigarettes between classes, and who knows what else they may have done, but it wasn’t something that affected me. They were a tiny minority, and the sad stories from the rest of their lives made it obvious that they were people to be friended, not emulated.

Gary and I were insulated from all this anyway. Neither of us would have tried smoking even if we’d had the opportunity. It seemed dangerous, a sin that crossed a line that couldn’t be uncrossed.

One kid, who we nicknamed Jesus because of his long hair and beard, seemed to be an important influence on the behind-the-bleachers crowd. I remember him because his first name, Richard, meant that we were sometimes compared and contrasted, and because he sat behind me in history class, where he enjoyed poking my back with his sharp pencil. I didn’t know him well, although as with most people in Neillsville we had a connection. His mother, divorced, lived on our street and showed some interest in our church. When in an attempt to be friendly I happened to mention that connection to him, he warned me sternly never to speak of it to anyone. He hated church, he said, (and his mother?) so he didn’t want any association whatsoever to come back to him.

Years later I learned that he had been killed, murdered in some uncharacteristic small town violence in which he was found cut gruesomely into pieces, supposedly caught in a drug deal gone bad.